Combined

Spinal-Epidural Anesthesia

Joseph Eldor, MD

Preface

Origin

Soresi technique

Curelaru technique

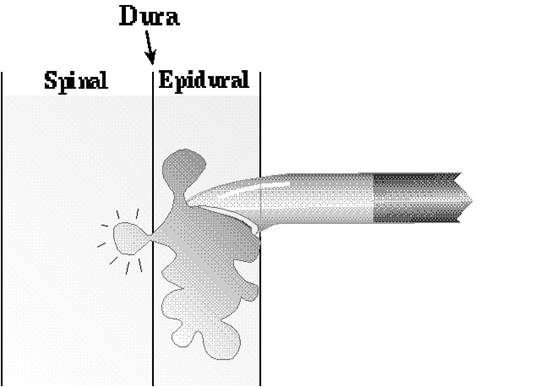

Needle-through-needle

technique

Eldor needle technique

Huber needle technique

Eldor, Coombs and

Torrieri technique

Indications

Problems

The twin theory

Failed spinal or

epidural anesthesia

One needle technique

for combined spinal-epidural anesthesia

Aspiration pneumonia

prevention by the CSEA

Intraoperative

challenges

Anesthesia and public

image

Huber needle and Tuohy

catheter

Total spinal

anesthesia: The origin of CSEGA

What is anethesia?

Use of ephedrine in

CSEGA

Cardiovascular effects

of CSEGA

Cord ischemia and

preemptive analgesia

CSEA for Cesarean

section

Corning

Bier

A new look at the

lumbar extradural space pressure

Do not rotate the

epidural needle

Epidural rostal

augmentation of spinal anesthesia

Metallic particles in

the needle-through-needle technique

Superselective spinal

anesthesia

CSEA in uncommon

disease

CSEA for laparoscopic

operations

Postoperative epidural

analgesia

Unilateral spinal

anesthesia

CSEA for abdominal

operations

CSEA for thoracic

operations

Anesthetic risk

factors

Medico-legal aspects

of CSEA

Spinal opioid pruritus

and emesis

Endocrine responses to

spinal or epidural anesthesia

Epidural unilateral

blockade

Combined

spinal-epidural anesthesia: The anesthesia of choice

Epidural catheter

strength

Epidural catheter

paresthesias

CSEA and anticoagulation

Combined

spinal-epidural analgesia in labor

Combined

spinal-epidural anesthesia for orthopedic operations

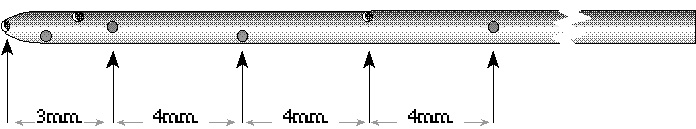

Combined end-multiple

lateral holes (CEMLH) epidural catheter

Double-hole

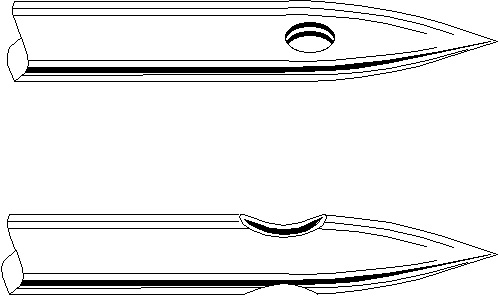

pencil-point spinal needle

Epidural catheter test

dose in the combined spinal-epidural anesthesia

Spinal and epidural

opioid analgesia

The choice of the

anesthesiologists

Epidural catheter

malposition

Woolley and Roe case

Anesthetic costs

From the skin to the

spinal-epidural spaces

Myint case

Spinal needles

Meningitis post

spinal-epidural anesthesia

Preemptive analgesia

and combined spinal-epidural anesthesia

Sympathetic

innervation and CSEA

The politics of

anesthesiology

Preconclusion

Conclusion

CSEA (combined

spinal-epidural anesthesia) and CSEGA (combined spinal-epidural-general

anesthesia) are new modalities of anesthesia for almost any patient at any age.

This book highlights the subject from various points of view. It doen`t intend

to teach. It`s goal is to encourage the anesthesiologists to practise what they

already know in the best way they think is good for themselves while being a

patient. It is a kind of a balanced anesthesia which uses techniques instead of

drugs to accomplish the ideal kind of anesthesia for the patients. This new

frontier in anesthesia should open a new era of anesthetic quality and

cost-effectiveness. However, in the second edition of Principles and Practice

of Obstetric Analgesia and Anesthesia, edited by Bonica JJ and McDonald JS, and

published in 1995 by Williams & Wilkins, there are 1344 pages. The chapter

on epidural analgesia and anesthesia contains 127 pages. That

on subarachnoid block - 26 pages. On subarachnoid/epidural combination

there is only half a page with only 2 references in the chapter on cesarean

section. So, the new combined spinal-epidural anesthesia gained only 0.03% of

the space in a book published in 1995 on the practice of obstetric analgesia

and anesthesia. This is really not its present worth, neither its future...

"It has long been an axiom of mine that the little things are infinitely

the most important" (Arthur Conan Doyle).

"If pain could have cured us we should long ago have been saved"

(George Santayana).

"The greatest evil is physical pain" (St. Augustine of Hippo).

Origin

The first epidural analgesia was done by 1. Corning JL. Spinal

anaesthesia and local medication of the cord. NY Med J 1885;42:483-485 2. Wynter WE. Lumbar

puncture. Lancet 1891;1:981-982 3. Quincke HI. Die technik der

lumbalpunktion. Verh Dtsch Ges Inn Med 1891;10:321-331

4. Von Ziemssen HW. Allgemeine

behandlung der infektionskrankenheiten. 5. Bier A. Versuche uber Cocainisirung

des Ruckenmarkes. Dtsch Ztschr Chir 1899;51:361-369 6. Soresi AL. Episubdural anesthesia.

Anesth Analg 1937;16:306-310 7. Curelaru I. Long duration subarachnoid

anaesthesia with continuous epidural block. Praktische Anasthesie

Wiederbelelung und Intensivtherapie 1979;14:71-78 8. Genesis 2:21 9. Ecclesiastes 4:9 Soresi

technique Soresi (1) used a fine needle without

stilet and introduced it into the epidural space using the hanging drop

technique. While in the epidural space he injected 7-8 ml of dissolved novocain. Then he pierced the dura and poured another 2 ml

of dissolved novocain into the spinal space. This gave

his patients anesthesia for a period of 24-48 hours! He and his colleagues

employed this method in over 200 patients. He concluded that "by combining

the two methods many of the disadvantages of both methods are eliminated and

their advantages are enhanced to an almost incredible degree". 1. Soresi AL. Episubdural anesthesia.

Anesth Analg 1937;16:306-310 Curelaru

technique Forty two years later, the Swedish anesthesiologist,

Curelaru (1), while working in 1. Curelaru I. Long duration

subarachnoid anaesthesia with continuous epidural block. Praktische Anasthesie

Wiederbelelung und Intensivtherapie 1979;14:71-78 Nedle-through-needle

technique Coates (1) from 1. Coates MB. Combined

subarachnoid and epidural techniques. A single space

technique for surgery of the hip and lower limb. Anaesthesia 1982;37:89-90 2. Mumtaz MH, Daz M, Kuz M. Combined

subarachnoid and epidural techniques: Another single space technique for

orthopaedic surgery. Anaesthesia 1982;37:90 Eldor

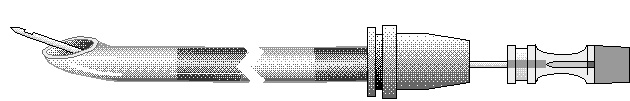

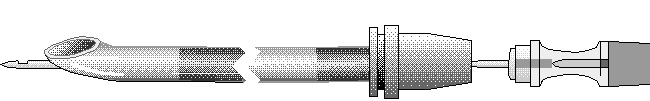

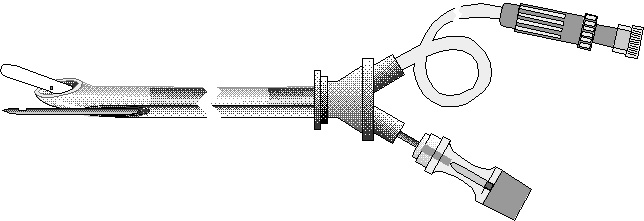

needle technique The Eldor needle (1) was first described

in 1990. The Eldor needle is a combined spinal-epidural needle which is

composed of an 18 gauge epidural needle with a 20 gauge spinal conduit. This is

a specialized needle for the combined spinal-epidural anesthesia. There is no

need of long spinal needles. The epidural catheter can be inserted before the

spinal anesthetic injection. The Eldor needle facilitates the insertion of very

small gauge spinal needles through its spinal conduit, so significantly reduces

the incidence of post-dural puncture headache. There is no danger of epidural

catheter protrusion through the dural hole made by the spinal needle. There are no metallic particles production while the spinal needle

passes through the bent epidural needle tip, as in the needle-through-needle

technique. The procedure of the Eldor needle is quite simple and

straightforward. First, the spinal needle is introduced into the guide needle

as far as the distal end of the latter. Then, the now Eldor needle is

introduced into the selected intervertebral space and the epidural space is

located using the well-known indicator methods. After that the epidural

catheter is introduced into the epidural space, confirming its position by the

test dose technique. Then, the spinal needle is slowly pushed in to puncture

the dura, until cerebrospinal fluid is obtained. The anesthetic solution is

injected through the spinal needle into the spinal space. Subsequently, the

spinal needle is slowly withdrawn from the guide needle and then the Eldor

needle is withdrawn, leaving the epidural catheter in position in the epidural

space. 1. Eldor J, Guedj P. Une nouvelle

auguille pour l`anesthesie rachidienne et peridurale

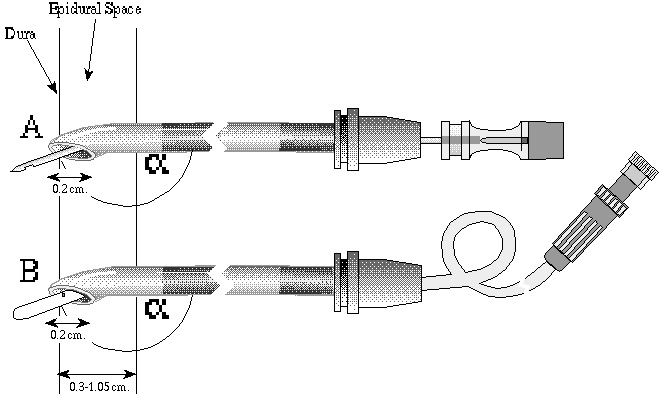

conjointe. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim 1990;9:571-572 Huber

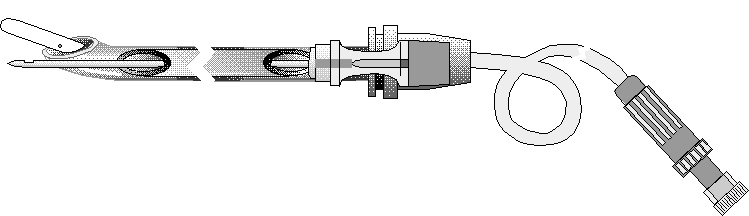

needle technique Huber (1), the inventor of the

"Tuohy" epidural needle, also patented in 1953 an

hypodermic needle with an "auxiliary outlet being disposed in transverse

alignment with the channel outlet" (2). Hanaoka (3) described in 1986 its

use in 500 patients. This needle has a very small hole behind the epidural

needle tip ("back eye"). A small gauge spinal needle is inserted

through that hole and punctures the dura. After withdrawing the spinal needle

an epidural catheter is introduced through the epidural needle. 1. Eldor J. Huber needle and Tuohy

catheter. Reg Anesth 1995;20:252-253 2. Huber RL. Hypodermic

needle. US Patent No. 2,748,769 3. Hanaoka K. Experience in the use of

Hanaoka`s needles for spinal-continuous epidural anaesthesia (500 cases). 7th Asian Australasian Congress of Anaesthesiologists Abstracts.

Eldor,

Coombs and Torrieri technique Eldor (1) and Torrieri (2) described in

separate letters, in 1988, an epidural needle with a

spinal needle attached to it. Through the spinal needle a longer spinal needle

is inserted into the subarachnoid space, while an epidural catheter is

introduced through the epidural needle into the epidural space. A few months

before the publication of these letters, Coombs (3) applied for a patent on the

same device. 1. Eldor J, Chaimsky G. Combined

spinal-epidural needle (CSEN). Can Anaesth Soc J 1988;35:537-8

2. Torrieri A, Aldrete JA. Letter to the Editor. Acta Anaesthesiologica Belgica 1988;39:65-66 3. Coombs DW. Multi-lumen

epidural-spinal needle. US Patent No. 4,808,157 Indications Combined spinal-epidural anesthesia is

like "to paint the fence" from both its sides. The indications are

those of the spinal or epidural alone and even more. Rawal (1) made a survey in

17 European countries on their anesthetic choices in 1992. 17% of the

procedures were performed under central blocks. Among these blocks - 56% were

spinal; 40% - epidural and 4% - combined spinal-epidural anesthesia. The

commonest indication for combined spinal-epidural blocks was hip replacement

surgery (28.2%), followed by hysterectomy (19%), knee surgery (14.4%), Cesarean

section (14%), emergency Cesarean section (13%), femur fracture in elderly

patients (7.2%) and prostatectomy (5.6%). This under-utility of regional

anesthesia (only 17% of the procedures) is in contrast to how the

anesthesiologists would like to be anesthetized in case they need an operation:

In 1986, Broadman et al. (2) confirmed that 92% of the anesthesiologists

preferred regional over general anesthesia for their own hypothetical surgery,

while 74% preferred a regional technique for their own elective extremity

surgery. This is in accordance with a previous survey done in 1973 by Katz (3)

in which 68% of the American anesthesiologists

surveyed preferred regional anesthesia for their own anesthetic during an

unspecified elective surgical procedure. The spectrum of indications for the

combined spinal-epidural anesthesia ranges from labor analgesia (4,5) to high abdominal and even thoracic and head operations

(6) by the adjuvant use of an endotracheal tube ventilation. The dosages of the

local anesthetics with or without opioids that are injected into the spinal and

epidural spaces are now evaluated in various hospitals around the world. The

dosage combinations are enormous. The story has only begun. 1. Rawal N. European trends in the use of

combined spinal epidural technique - A 17-nation survey. Reg Anesth 1995;20 (Suppl):162 2. Broadman LM, Mesrobian R, Ruttiman U, 3. Katz J. A survey of

anesthetic choice among anesthesiologists. Anesth Analg 1973;52:373-5 4. Abouleish A, Abouleish E, Camann W.

Combined spinal-epidural analgesia in advanced labour. Can J Anaesth 1994;41:575-8 5. Arkoosh VA, Sharkey SJ, Norris MC,

Isaacson W, Honet JE, Leighton BL. Subarachnoid block analgesia: Fentanyl and

morphine versus fentanyl and morphine. Reg Anesth 1994;19:243-246

6. Eldor J. Combined

spinal-epidural-general anesthesia. Reg Anesth 1994;19:365-6

Problems Blumgart et al. (1) found that the

mechanism of extension of spinal anesthesia by extradural injection of local anesthetics

is largely a volume effect. Using extradural saline 10 ml and extradural

bupivacaine 0.5% 10 ml - the extension of the block was found to be similar in

the saline or the bupivacaine groups, and significantly faster than the group

which received no extradural injection after spinal injection of 1.6-1.8 ml of

0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine. Suzuki et al. (2) found that spinal puncture with

a 26 gauge spinal needle, with no spinal anesthetic injection, immediately

before epidural injection of 18 ml 2% mepivacaine resulted in rapid caudal

spread of analgesia as compared to an epidural anesthetic alone. They

attributed it to the flow of local anesthetic into the subarachnoid space

through the perforation produced by the spinal needle. In all the techniques,

except the Eldor needle and Curelaru`s double-space techniques, there is

inability to perform the epidural catheter test dose due to the fact that the

epidural catheter is inserted after the subarachnoid local anesthetic

injection. This can result in epidural catheter malposition in the subarachnoid

space or intravascular with a danger of total spinal, delayed cardiorespiratory

arrest due to opioid overdosage (3,4) or convulsions.

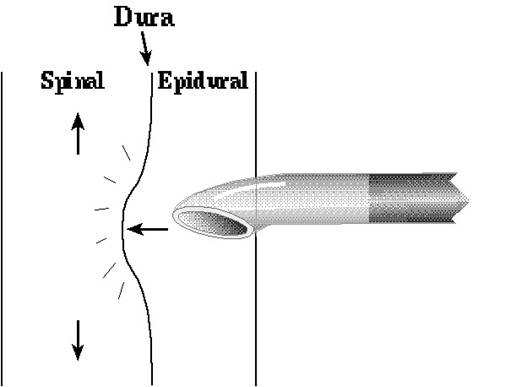

Due to the insertion of the spinal needle through the bent tip of the epidural

needle in the needle-through-needle technique there is friction that produces

metallic microparticles that can be introduced further into the epidural space

by the epidural catheter insertion (5,6). If there is

a delay in epidural catheter threading in the needle-through-needle technique

there is a partial spinal anesthesia while using the hyperbaric anesthetic

solution (7), with the need to supplement it further through the epidural

route. The incidence of epidural needle or catheter unintentional dural

puncture ranges from 2.5% (8) to 0.6% (9) and even 0.26% (10). However, using

the needle-through-needle technique the chances are greater because of the same

pathway shared by the spinal needle and the epidural catheter in the epidural

space and the force exerted by the friction between the spinal needle and the

epidural needle`s tip that can advance forward the epidural needle causing an

unrecognized dural tear by the epidural needle, through which an epidural

catheter can be threaded inadvertently. 1. Blumgart CH, Ryall D, Dennison B,

Thompson-Hill LM. Mechanism of extension of spinal

anaesthesia by extradural injection of local anaesthetic. Br J Anaesth

1992;69:457-460 2. Suzuki N, Koyanemaru M, Onizuka S,

Takasaki M. Dural puncture with a 26-gauge spinal needle affects epidural

anesthesia. Reg Anesth 1995;20 (Suppl):118 3. Myint Y, Bailey PW, Milne BR.

Cardiorespiratory arrest following combined spinal epidural anaesthesia for

caesarean section. Anaesthesia 1993;48:684-686 4. Eldor J, Guedj P, Levine S. Delayed

respiratory arrest in combined spinal-epidural anesthesia. Reg Anesth 1994;19:418-422 5. Eldor J, Brodsky V. Danger of metallic

particles in the spinal-epidural spaces using the needle-through-needle

approach. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 1991;35:461 6. Eldor J. Metallic particles in the

spinal-epidural needle technique. Reg anesth 1994;19:219-220

7. Fan SZ, Susetio L, Wang YP, Cheng YJ, Liu CC. Low dose of intrathecal hyperbaric bupivacaine

combined with epidural lidocaine for cesarean section - a balance block

technique. Anesth Analg 1994;78:474-7 8. Dawkins CJM. An

analysis of the complications of extradural and caudal block.

Anaesthesia 1969;24:554-563 9. Tanaka K, Watanabe R, Harada T, Dan K.

Extensive application of epidural anesthesia and analgesia in a university

hospital: Incidence of complications related to technique. Reg Anesth 1993;18:34-38 10. Macdonald R, Lyons G. Unintentional

dural puncture, Anaesthesia 1988;43:705 The twin

theory Spinal anesthesia is a safe,

cost-effective and reliable form of anesthesia. Many anesthesiologists would

regard the epidural as an insurance against unsatisfactory spinal anesthesia,

aiming to provide complete anesthesia by the subarachnoid route (1). Another

approach is the use of a minimal dose of spinal anesthesia for a shorter

duration with the flexibility of epidural reinforcement if necessary. For many

years in many anesthetic departments around the world there was a philosophy

that extradurals are for young people and the intrathecal route for the old,

with few exceptions. Seeberger et al. (2) addressed the question: Is the spinal

or the epidural technique better? Two hundred and two patients younger than 50

years underwent spinal or epidural anesthesia. Spinals were performed with

24-gauge Sprotte needles and epidurals with 18 gauge Tuohy needles and

catheters. The failure rate of both techniques was 5%. Patient acceptance was

high in both groups (97% in the spinal; 93% in the epidural). The authors

concluded that spinal anesthesia was superior, because of better quality of

anesthesia, no risk of intoxication, less time needed to perform the block, and

less expensive kits. However, using the combined spinal-epidural anesthesia

there is no more a question of which is better, as Greene and Brull (3) wrote:

"Epidural and spinal anesthesia are indeed related to each other, but only

to the same extent as cousins, or, at best, siblings; monozygotic twins they

are not". 1. Brownridge P. Epidural and

subarachnoid analgesia for elective caesarean section. Anaesthesia 1981;36:70 2. Seeberger MO, Lang ML, Drewe J,

Schneider M, Hauser E, Hruby J. Comparison of spinal and epidural anesthesia

for patients younger than 50 years of age. Anesth Analg 1994;78:667-73

3. Failed

Spinal or Epidural Anesthesia Failure of regional anesthesia has been

reported to be in the order of 4% (1,2). The failure

rate of spinal anesthesia alone ranged between 3.1% - 17% involving 100 to

1,891 patients respectively (3,4). Johr et al. (5)

investigated the incidence of failed spinal anesthesia in a Swiss teaching

institution. Of 3,004 blocks 197 (6.5%) did not provide satisfactory analgesia.

The 197 failures included: absent blockade - 36; failure to obtain CSF - 6;

level too low - 90; duration too short - 36; intensity too weak - 28; unclear -

1. However, 531 (17.4%) blocks were excessively high (45 - cervical level; 2 -

required intubation). The management of the 197 failed blocks included:

additional spinal anesthesia - 117; epidural anesthesia - 2; local infiltration

- 1; general anesthesia - 30; IV supplementation - 47. Manchikanti et al. (6)

found that the failure rate with sole use of spinal anesthesia ranges between

0.46% and 35% . Epidural analgesia sometimes falls

short of perfection due to the variable "compartmentalisation" of the

epidural space (7). Shesky et al. (8) studied in 1983 the dose-response of

bupivacaine for spinal anesthesia. Sixty males having transurethral surgery

were studied using 10-, 15- and 20 mg doses of glucose-free bupivacaine as

either a 0.5 or a 0.75% solution. Both 15 and 20 mg of either concentration of

bupivacaine provided satisfactory spinal anesthesia. However, three of 20

patients receiving 10 mg dose required supplementation with general anesthesia.

Lyons et al. (9) used a 26G spinal needle through the Tuohy epidural needle for

the combined spinal-epidural anesthesia. Unsuccessful spinal anesthesia

occurred in 8 of the 50 patients (16%). In four patients, anesthesia was

provided by the epidural route, while in the remainder another intrathecal

injection was made using a different intervertebral space. Lesser et al. (10)

evaluated the use of a 30G spinal needle through the Tuohy epidural needle for

the combined spinal-epidural anesthesia. Unsuccessful spinal anesthesia was in

12 of the 50 patients (24%) studied. Six failures were due to unsuccessful

dural puncture and six to inadequate block. Due to requirement of large doses

of local anesthetics for epidural block there is a risk of toxic complications

(11,12). In spite of large doses epidural block may

fail to provide adequate analgesia in up to 25% of patients due to difficulty

in blocking sacral roots (13-15). Failure to obtain CSF when using the

needle-through-needle technique may occur despite successful dural puncture if

the needle orifice is occluded, for example by a nerve root. It may also happen if dural puncture has failed to occur because the

spinal needle is too short or is placed too laterally as the epidural needle

may have entered the epidural space at an angle (16). One technical

problem of the needle-through-needle method is the occasional difficulty in

threading the catheter into the epidural space after injection of the spinal

solution. If some minutes are spent in replacing the epidural needle, the

spinal solution may become relatively "fixed" on the dependent side

(17). However, when spinal and epidural anesthesia are combined, recourse to

general anesthesia becomes a very rare event. 1. Milne MK, Lawson JIM. Epidural analgesia for Caesarean section. A

review of 182 cases. Br J Anaesth 1973;45:1206-10

2.Moir DD.

Local anaesthetic techniques in obstetrics. Br J Anaesth 1986;58:747-59.

3. Tarkkila PJ. Incidence and causes of failed spinal anesthetics in a

university hospital: a prospective study. Reg Anesth 1991;16:48-51

4. Levy JH, Islas JA, Ghia JN, Turnbull

C. A retrospective study of the incidence and causes of

failed spinal anesthetics in a university hospital. Anesth Analg 1985;64:705-10 5. Johr M, Hess FA, Balogh S, Gerber H.

Incidence and management of failed spinal anaesthesia in a teaching

institution: A prospective evaluation of 3,004 epidural blocks. Acta

Anaesthesiol Scand 1995;39:A421 6. Manchikanti L, Hadley C, Markwell SJ,

Colliver JA. A retrospective analysis of failed spinal

anesthetic attempts in a community hospital. Anesth Analg 1987;66:363-6. 7. Husemeyer RP, 8. Sheskey MC, Rocco AG, Bizzari-Schmid

M, Francis DM, Edstrom H, Covino BG. A dose-response study of

bupivacaine for spinal anesthesia. Anesth Analg 1983;62:931-5.

9. Lyons G, Macdonald R, Mikl B.

Combined epidural/spinal anaesthesia for Caesarean section: Through the needle

or in separate spaces? Anaesthesia 1992;47:199-201. 10. Lesser P, Bembridge M, Lyons G,

Macdonald R. An evaluation of a 30-gauge needle for spinal

anaesthesia for Caesarean section. Anaesthesia 1990;45:767-8.

11. Abouleish E, Bourke D. Concerning

the use and abuse of test doses for epidural anesthesia. Anesthesiology 1984;61:344-5. 12. Thorburn J, Moir DD. Bupivacaine

toxicity in association with extradural analgesia for Caesarean section. Br J

Anaesth 1984;56:551-3. 13. Larsen JV. Obstetric

analgesia and anaesthesia. Clinics in Obst Gyn 1982;9:685-710.

14. Thorburn J, Moir DD. Epidural

analgesia for elective Caesarean section. Technique and its

assessment. Anaesthesia 1980;35:3-6. 15. Kileff ME, James FM, Dewan DM, Floyd

HM. Neonatal neurobehavioral responses after epidural anesthesia for Cesarean

section using lidocaine and bupivacaine. Anesth Analg 1984;63:413-7.

16. Patel M, Samsoon G, Swami A, Morgan

BM. Flow characteristics of long spinal needles. Anaesthesia 1994;49:223-225. 17. Carrie LES. Epidural

versus combined spinal epidural block for Caesarean section. Acta

Anaesthesiol Scand 1988;32:595-596. One

needle technique for combined spinal-epidural anesthesia Vitenbeck (1), in 1980, described the

use of combined spinal-epidural anesthesia in 210 patients using the same

needle for the spinal and the epidural injections. He first injected 1-2 ml

Dicaine 0.2% into the subarachnoid space. Five minutes later he injected

through the same needle, which was withdrawn into the epidural space, 25-37 ml

of Dicaine 0.2-0.3% in distilled water with adrenaline 1:1,000. Anesthesia

lasted for 2.5-3.5 hr. In only 3 patients he needed to induce general

anesthesia because the operation lasted more than the effect of the regional

anesthesia. Only 2 patients (0.9%) had postdural puncture headaches. 1. Vitenbeck IA. Associated

spino-peridural anesthesia as a variant of conduction anesthesia during

operation. Vestn Khir 1981;126:123-128. Aspiration

pneumonia prevention by the CSEA In a review of maternal mortality

published in 1991 (1) Glassenberg quoted statistics collected up to the

mid-1980`s in the UK, USA and Sweden. Over the preceding decade, aspiration as

a cause of maternal death had fallen to two deaths per million births, or one

death per 30,000 anesthetics, still seven times the aspiration fatality rate

for the non-obstetric surgical population, and closely associated with failed

intubation. Dennis W. Coombs (2) wrote in 1983 an editorial entitled

"Aspiration pneumonia prophylaxis". He said that "unfortunately,

the magic prophylactic bullet is not available yet for all situations".

However, instead of a "cimetidine prophylaxis" it is suggested to use

the "CSEA prophylaxis"... 1. Glassenberg R. General anaesthesia

and maternal mortality. Semin Perinatol 1991;15:386-396.

2. Coombs DW. Aspiration

pneumonia prophylaxis. Anesth Analg 1983;62:1055-8.

Intraoperative

challenges Although developments in anesthesia and

surgery have improved overall surgical outcome during recent decades, there is

still concern about the detrimental effects of operative procedures, such as

myocardial infarction, pulmonary complications, thromboembolism,

gastrointestinal paralysis, immunosuppression,etc., that cannot be attributed

solely to imperfections in surgical technique (1). Edwards et al. (2) studied

100 patients undergoing transurethral surgery, who were allocated randomly to

receive either general or spinal anesthesia. The overall incidence of

myocardial ischemia increased from 18% to 26% between the preoperative and

postoperative periods, but no significant difference between the two anesthetic

techniques. Nakatsuka et al. (3) used spinal anesthesia combined with epidural

anesthesia in nine patients with ischemic heart disease having femoral-distal

artery bypass surgery. A 20-gauge epidural catheter and a 24-gauge spinal

catheter were inserted. Epidural anesthesia was initiated using 10-12 ml of 2%

lidocaine and switched to continuous epidural anesthesia with 0.5% bupivacaine

(5-7 ml/hr). Spinal bupivacaine 0.75% was injected up to 5 mg through the

spinal catheter as needed to manage surgical pain of lower leg and foot. Seven

out of 9 patients required additional spinal anesthesia. Juelsgaard et al. (4)

examined continuous spinal anesthesia vs single dose spinal anesthesia vs

general anesthesia in 44 elderly patients scheduled for hip surgery and

receiving medication for angina or displaying ECG signs of coronary sclerosis.

In the continuous spinal anesthesia they injected 1.5 ml isobaric bupivacaine

0.5% with 0.5 ml increments to establish T10 anesthesia. In the single dose

spinal anesthesia group they injected 2.5 ml isobaric bupivacaine 0.5%. The

general anesthesia consisted of fentanyl, thiopentone, N2O/O2 and enflurane.

There were only 3 hypotensive events in the continuous spinal group (3/10

patients) compared to 24/13 patients in the single dose spinal group and 29/11

patients in the general anesthesia group. There was only 1 ischemic event in

the continuous spinal group compared to 93 ischemic events in the single dose

spinal and 1. Kehlet H. Postoperative pain relief:

A look from the other side. Reg Anesth 1994;19:369-377.

2. Edwards ND, Callaghan LC, White T,

Reilly CS. Perioperative myocardial ischemia in patients undergoing

transurethral surgery: a pilot study comparing general with spinal anaesthesia.

Br J Anaesth 1995;74:368-372. 3. Nakatsuka M, Long SP, Shy DG. Spinal

anesthesia combined with epidural anesthesia for peripheral vascular emergency

with dual catheters. Anesth Analg 1994;78:S309. 4. Juelsgaard P, Sand NPR, Felsby S,

Dalsgaard J, Brink O, Thygesen K. Continuous spinal anaesthesia vs single dose

spinal anaesthesia vs general anaesthesia: Perioperative holter monitoring of

patients with coronary atherosclerosis. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 1995;39:A428 Anesthesia

and public image Swinhoe and 1. Swinhoe CF, 2. Gajraj NM, 3. Ali S, Vivekanaandan P, Tierney E.

Patient`s perception of the anaesthetist and anaesthesia. Anaesthesia 1994;49:644-5. 4. Keep PJ, Jenkins JR. As others see us. The patient`s view of the anaesthetist.

Anaesthesia 1978;33:43-5. 5. Katz J. A survey of

anesthetic choice among anesthesiologists. Anesth Analg 1973;52:373-5. 6. Broadman LM, Mesrobian R, Ruttiman U,

Huber

needle and Tuohy catheter On April 23, 1941, Edward B. Tuohy (1)

presented his experience of continuous spinal anesthesia in the Proceedings of

the Staff Meetings of the Mayo Clinic. The method of continuous spinal

anesthesia was first used in the Mayo Clinic in November 1940 according to the

technic and equipment advocated by William T. Lemmon (2). It consisted of a

special operating table mattress, special spinal needles, 18 gauge,

with stylet, which were soft and malleable, a 10 ml Luer-lok syringe with

special stopcock connections and rubber tubing to connect the spinal needle

with the glass syringe. The rubber-covered mattress had a gap 1. Tuohy EB. Continuous

spinal anesthesia. Proceedings of the Staff Meetings of the Mayo Clinic

1941;17:257-259. 2. Lemmon WT. A method

for continuous spinal anesthesia. Ann Surg 1940;111:141-144.

3. Tuohy EB. Continuous spinal

anesthesia: its usefulness and technic involved. Anesthesiology 1944;5:142-148. 4. 5. Manalan SA. Caudal

block anesthesia in obstetrics. J 6. Love JG. Continuous

subarachnoid drainage of meningitis by means of a ureteral catheter.

JAMA 1935;104:1595. 7. Tuohy EB. The use

of continuous spinal anesthesia utilizing the ureteral catheter technic.

JAMA 1945;128:262-264. 8. Tuohy EB. Continuous spinal

anesthesia: A new method utilizing a ureteral catheter. Surg Clins N. Am 1945;25:834-840. 9. Cousins MJ, Bridenbaugh 11. Winnie AP. A

letter to Ostheimer GW. March 17, 1994. Total

spinal anesthesia: The origin of CSEGA Evans (1) described in 1928 the possible

complications of spinal anesthesia. Concerning respiratory paralysis he

wrote:" If respiration should cease , keep cool.

Raise the lower jaw, pull the tongue forward and begin artificial respiration

at a uniform rate. Mouth to mouth insufflation is the most convenient and

efficacious method of artificial respiration". Twenty years before, in

September 1908, before the Congress of the International Society of Surgery, in

1. Evans CH. Possible complications with

spinal anesthesia. Their recognition and the measures employed to prevent and

to control them. Am J Surgery 1928;5:581-593. 2. Jonnesco T. Remarks on general spinal

analgesia. Br Med J 1909;2:1396-1401. 3. Jonnesco T. Concerning general

rachianesthesia. Am J Surgery 1910;24:33 4. Koster H, Kasman LP. Spinal

anesthesia for the head, neck and thorax: its relation to respiratory

paralysis. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1929;49:617. 5. Vehrs GR. Spinal anesthesia: Technic

and clinical application. 6. Jones RGG. A

complication of epidural technique. Anaesthesia 1953;8:242.

7. Huvos MC, Greene NM, Glaser GH.

Electroencephalographic studies during acute subtotal denervation in man. Yale

J Biol Med 1962;34:592. 8. Greene NM. Hypotensive

spinal anesthesia. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1952;95:331.

9. Kendig JJ. Spinal

cord as a site of anesthetic action. Anesthesiology 1993;79:1161-2. 10. Bromage PR, Joyal AC, Binney JC.

Local anaesthetic drugs: Penetration from the spinal extradural space into the

neuraxis. Science 1963;140:392. 11. Evans TI. Total

spinal anaesthesia. Anaesth Intensive Care 1974;2:158-63.

12. Yamashiro H, Hirano K. Treatment

with total spinal block of severe herpetic neuralgia accompanying median and

ulnar nerve palsy. Masui 1987;36:971-5. 13. Gillies IDS, Morgan M. Accidental

total spinal analgesia with bupivacaine. Anaesthesia 1973;28:441-5.

14. DeSaram M. Accidental total spinal

analgesia. A report of three cases. Anaesthesia 1956;11:77. 15. Goda Y, Kimura T, Goto Y, Kemmotsu

O. Power spectral analysis of heart rate and peripheral blood flow variations

during total spinal anesthesia. Masui 1989;38:1275-81.

16. Palkar NV, Boudreaux RC, Mankad AV.

Accidental total spinal block : a complication of an

epidural test dose. Can J Anaesth 1992;39:1058-60. 17. Kimura T, Goda Y, Kemmotsu O,

Shimada Y. Regional differences in skin blood flow and temperature during total

spinal anaesthesia. Can J Anaesth 1992;39:123-7. 18.

Kobori M, Negishi H, Masuda Y, Hosoyamada A. Changes in respiratory

, circulatory, endocrine, and metabolic systems under induced total

spinal block. Masui 1991;40:1804-9. 19. Kobori M, Negishi H, Masuda Y,

Hosoyamada A. Changes in systemic circulation under induced total spinal block

and choice of vasopressors. Masui 1990;39:1580-5. 20. Matsuki M, Muraoka M, Oyama T. Total

spinal anaesthesia for a Jehovah`s Witness with primary aldosteronism.

Anaesthesia 1988;43:164-5. 21. Mets B, Broccoli E, What is

anesthesia? Definitions of the state of anesthesia:

1. Drug-induced unconsciousness; the patient neither perceives nor recalls

noxious stimulation (1). 2. Reversible oblivion and immobility (2). 3.

Paralysis, unconsciousness, and attenuation of the stress response (3). 4.

Sensory block, motor block, blocking of reflexes, and mental block (4). 5. All

separate effects used to protect the patient from the trauma of surgery (5).

Jorgensen et al. (6) studied the anesthetic choice of 705 patients of

outpatient surgery candidates prior to speaking to the anesthesiologist. Sixty

five percent preffered general anesthesia, 22% - spinal anesthesia, and 12%

were unsure. Of those who had spinal anesthesia previously, only 33% would

select it in the future. Conversely, 70% of patients who had general anesthesia

would prefer it again. Concerns about spinal anesthesia were

: paralysis, nerve damage, being awake, infection, inadequate

anesthesia, backache, fear of needle and headache. The use of regional

anesthesia in residency training programs has increased from 21.3% in 1980 to

29.8% in 1990, primarily because of a two-fold rise in the use of epidural

anesthesia (7). Advantages of spinal anesthesia: Obviates the need for deep

general anesthesia, profound muscle relaxation, cheap, easy to perform, danger

of toxic drug signs - negligible. Disadvantages of spinal anesthesia:

hypotension, postoperative headache, some patients prefer to be asleep during

operation. The combined spinal-epidural anesthesia combines the rapid onset and

good muscle relaxation of subarachnoid block with the ability to supplement

analgesia through the epidural catheter, intraoperatively and after the

operation. Reynolds et al. (8) using plain lumbar x-rays and CT after injection

of iodized oil into the extradural space of 19 subjects recorded the depth of

the extradural space at the caudal end: 8.3 ± 1. Prys-Roberts C. Anaesthesia: a

practical or impractical construct? Br J Anaesth 1987;59:1341-5.

2. 3. Pinsker MC. Anesthesia: a pragmatic

construct. Anesth Analg 1986;65:819-27. 4. Woodbridge PD. Changing concepts

concerning depth of anesthesia. Anesthesiology 1957;18:536-50.

5. Kissin I, Gelman S. Components of

anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth 1988;61:237-42. 6. Jorgensen NH, Harders M, Hullander

RM, Leivers D. Survey of preference for spinal vs.

general anesthesia: Education makes a difference. Reg Anesth 1993;18:S53. 7. Kopacz DJ, Bridenbaugh LD. Are anesthesia

residency programs failing regional anesthesia? The past,

present and future. Reg Anesth 1993;18:84-87. 8. Reynolds AF, Roberts PA, Pollay M,

Stratemeier PH. Quantitative anatomy of the thoracolumbar epidural space.

Neurosurgery 1985;17:905-907. 9. Westbrook JL, Renowden SA, Carrie

LES. Study of the anatomy of the extradural region using

magnetic resonance imaging. Br J Anaesth 1993;71:495-498.

10. Pitkin GP. Controllable

spinal anesthesia. Am J Surg 1928;5:537-553. 11. Koster H. Spinal anesthesia, with

special reference to its use in surgery of the head, neck and thorax. Am J Surg

1928;5:554-570. 12. Babcock WW. Spinal

Anesthesia. An experience of twenty-four years.

Am J Surg 1928;5:571-6. 13. Bromage PR. Physiology and

pharmacology of epidural analgesia. Anesthesiology 1967;28:592-622.

14. Use of

Ephedrine in CSEGA Ephedrine is the sympathomimetic drug

which is most widely used to sustain blood pressure during spinal anesthesia.

The active principal was isolated from the chinese

herb ma huang in 1885 by Yamanashi (1). Butterworth et al. (2) found that a

mixed adrenergic agonist such as ephedrine more ideally corrected the

noncardiac circulatory sequelae of total spinal anesthesia in dogs than did

either a pure alpha (phenyl-ephrine) or a pure beta-adrenergic agonist

(isoproterenol). Butterworth et al. (3) also demonstrated in dogs the

effectiveness of dobutamine and dopamine as possible alternatives to ephedrine

for the pharmacologic correction of the noncardiac circulatory sequela of total

spinal anesthesia. Goertz et al. (4) investigated the effect of ephedrine on

left ventricular function in patients without cardiovascular disease under high

thoracic epidural analgesia combined with general anesthesia. Ephedrine

improved left ventricular contractility without causing relevant changes of

left ventricular afterload. 1. Goodman L, Gilman A. The pharmacological basis of therapeutics. 2. Butterworth JF, Piccione Jr W,

Berrizbeitia LD, Dance G, Shenim RJ, Cohn LH. Augmentation of

venous return by adrenergic agonists during spinal anesthesia. Anesth

Analg 1986;65:612-6. 3. Butterworth JF,

Austin JC, Johnson MD, Berrizbeitia LD, Dance GR, Howard G, Cohn LH. Effect of total spinal anesthesia on arterial and venous responses

to dopamine and doputamine. Anesth Analg 1987;66:209-14.

4. Goertz AW, Hubner C, Seefelder C,

Seeling W, Lindner KH, Rockemann MG, Georgieeff M. The effect of ephedrine

bolus administration on left ventricular loading and systolic performance

during high thoracic epidural anesthesia combined with general anesthesia.

Anesth Analg 1994;78:101-5. Cardiovascular

effects of CSEGA Combining epidural analgesia with

general anesthesia in humans reduces the hemodynamic demand on the heart (1-3)

and provides more stable intraoperative hemodynamics (4). In animal experiments

epidural analgesia has inhibited sympathetic coronary constriction secondary to

a flow-limiting stenosis (5), reduced infarct size (6) and reduced ST-segment

changes on the electrocardiogram in an acute coronary artery occlusion model

(7). However, Mergner et al. (8) investigated epidural analgesia combined with

general anesthesia in a swine model with a tight coronary artery stenosis.

Distal to the coronary stenosis was a moderate

decrease in regional myocardial function and a severe reduction in blood flow.

The epidural analgesia reaching the level of T1 was added to an animal which

already had a decreased blood pressure and sympathetic tone from the

isoflurane/fentanyl anesthesia. No correction of the reduced blood pressure was

done in this study. Stenseth et al. (9) investigated the cardiovascular and

metabolic effects of T1-T12 epidural block in 18 patients receiving chronic

beta-adrenergic blocker medication and scheduled for aortocoronary bypass

surgery. Thoracic epidural analgesia induced a moderate decrease in mean

arterial pressure, coronary perfusion pressure, free fatty acids and myocardial

consumption of free fatty acids. Blomberg et al. (10,11)

also found no cardiac effects after a T1-T8 or T1-T6 block in beta-adrenergic

blocked patients with ischemic heart disease. Christensen et al. (12) evaluated

myocardial ischemic events by Holter monitoring of ST-segment depression in 14

patients with angina pectoris given spinal analgesia for minor surgery.

Ephedrine in doses of 5 mg was given, if rapid

infusion of saline did not improve the arterial pressure.The first ischemic

event occurred at a mean of 338 minutes after spinal analgesia, and not in

association with the onset of block, with the decrease in mean arterial

pressure after spinal analgesia or with the administration of ephedrine. This

could be explained by increased cardiac pre- and afterload, probably further

aggravated by the volume load. 1. Baron JF, Coriat P, Mundler O, et al. Left

ventricular global and regional function during lumbar epidural anesthesia in

patients with and without angina pectoris: influence of volume loading. Anesthesiology

1987;66:621-7. 2. Diebel LN, Lange MP, Schneider F, et

al. Cardiopulmonary complications after major surgery: a role for epidural

analgesia. Surgery 1987;102:660-6. 3. Yeager MP, Glass DD, Neff RK,

Brinck-Johnson T. Epidural anesthesia and analgesia in high-risk surgical

patients. Anesthesiology 1987;66:729-36. 4. Her C, Kizelshteyr G, Walker V, et

al. Combined epidural and general anesthesia for abdominal aortic surgery. J

Cardiothorac Anesth 1990;4:552-7. 5. Heusch G, Deussen A, Thamer V.

Cardiac sympathetic nerve activity and progressive vasoconstriction distal to

coronary stenoses: feed-back aggravation of myocardial ischemia. J Auton Nerv

Syst 1985;13:311-26. 6. Davis RF, DeBoer LWV, Maroko PR.

Thoracic epidural anesthesia reduces myocardial infarct size after coronary

artery occlusion in dogs. Anesth Analg 1986;65:711-7. 7. Vik-Mo H, Ottesen S, Renck H. Cardiac

effects of thoracic epidural analgesia before and during acute coronary artery

occlusion in open-chest dogs. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 1978;38:737-46.

8. Mergner GW, Stolte AL, Frame WB, Lim

HJ. Combined epidural analgesia and general anesthesia induce ischemia distal

to a severe coronary artery stenosis in swine. Anesth Analg 1994;78:37-45. 9. Stenseth R, Berg EM, Bjella L, Christensen

O, Levang OW, Gisvold SE. The influence of thoracic epidural

analgesia alone and in combination with general anesthesia on cardiovascular

function and myocardial metabolism in patients receiving beta-adrenergic

blockers. Anesth Analg 1993;77:463-8. 10. Blomberg S, Emanuelsson H, Kvist H,

et al. Effects of thoracic epidural anesthesia on coronary arteries and

arterioles in patients with coronary artery disease. Anesthesiology 1990;73:840-7. 11. Blomberg S, Emanuelsson H, Ricksten

SE. Thoracic epidural anesthesia and central hemodynamics in patients with

unstable angina pectoris. Anesth Analg 1989;69:558-62.

12. Christensen EF, Sogaard P, Egebo K,

Bach LF, Riis J. Myocardial ischemia and spinal analgesia in patients with

angina pectoris. Br J Anaesth 1993;71:472-5. Cord

ischemia and preemptive analgesia Breckwoldt et al. (1) investigated the

effect of intrathecal tetracaine on the neurological sequelae of spinal cord

ischemia and reperfusion with aortic occlusion in rabbits. They found that

intrathecal tetracaine significantly and dramatically abrogated the

neurological injury secondary to spinal cord ischemia and reperfusion after

aortic occlusion at 30 minutes. Peripheral tissue injury provokes two kinds of

modification in the responsiveness of the nervous system: peripheral

sensitization and central sensitization. The optimal form of pain treatment may

be one that is applied both pre-, intra-, and postoperatively to preempt the

establishment of pain hypersensitivity during and after surgery. Woolf and

Chong (2) in their review of preemptive analgesia concluded that "although

evolution has conserved sensitization in humans, the capacity to inflict

`controlled injury` during surgery has clearly not been anticipated". 1.

Breckwoldt WL, Genco CM, Connolly RJ, Cleveland RJ, Diehl JT. Spinal cord

protection during aortic occlusion: Efficacy of intrathecal tetracaine. Am

Thorac Surg 1991;51:959-63. 2. Woolf CJ, Chong MS. Preemptive

analgesia - treating postoperative pain by preventing the establishment of

central sensitization. Anesth analg 1993;77:362-79. CSEA for

Cesarean section An increasing number of parturients wish

to be awake during cesarean section (1) and opt for regional rather than

general anesthesia. Spinal block is a simple technique which requires a small

dose of local anesthetic to provide surgical anesthesia (1,2)

with rapid, intense and reliable block without missed segments (1,3), greater

muscle relaxation (1) and minimal risk of drug toxicity to the mother as well

as to the fetus (3). For these reasons it has been proposed as the anesthetic

method of choice for emergent cesarean section (4). Visceral pain is a poorly

localized, dull and deep pain which is often accompanied by nausea, vomiting

and sweating. Instead of pain, some patients describe it as a feeling of

heaviness, pressure, tightness and/or squeezing. Alahuhta et al. (5) compared

the incidence of visceral pain in 46 patients undergoing elective cesarean

section under spinal or epidural anesthesia with 0.5% bupivacaine. Visceral

pain occurred in 12/23 patients in the spinal group and in 13/23 patients in

the epidural group. Rawal et al. (1) used the combined spinal-epidural

anesthesia in 15 parturients scheduled for cesarean section. With the patients

in the sitting position they injected 1.5-2 ml of 0.5% (7.5-10 mg) hyperbaric

bupivacaine through the spinal needle to achieve an S5-T8-9 block. After

withdrawing the spinal needle, the epidural needle was rotated and an epidural

catheter introduced through it. After aspiration for blood or spinal fluid,

0.5-1 ml saline was injected in the epidural catheter to test its patency.

15-20 min after the spinal injection, 0.5% plain bupivacaine 1.5-2 ml per

unblocked segment were injected till a T4-5 level was reached. The combined

mean total dose of bupivacaine was 40.2±4.24 mg. It means that only 5-7 ml of

0.5% bupivacaine injected through the epidural catheter were needed to rise the anesthetic level from T8-9, reached by the previous

spinal injection, to T3-4 achieved by the epidural augmentation. Riley et al.

(6) compared the spinal versus epidural anesthesia for cesarean section in

relation to time efficiency. They have found that patients who received

epidural anesthesia had significantly longer total operating room times than

those who received spinal anesthesia (101 ±20 vs 83 ±16 min). This was caused

by longer times spent in the operating room until surgical incision (46 ±11 vs

29±6 min). Supplemental intraoperative intravenous analgesics and anxiolytics

were required more often in the epidural group (38%) than in the spinal group

(17%). Vucevic and Russell (7) compared 12 ml 0.125% plain bupivacaine with 3

ml 0.5% plain bupivacaine for cesarean section in 40 women using the combined

spinal-epidural technique. The initial spread was greater with the 12 ml

solution but within 5 min of placing the women in the supine tilted (right hip

up) position, there were no differences in the levels of sensory blockade. The

study also showed that the 12 ml solution resulted in more intensive blockade

as there was less need for extradural anesthesia in this group than in the 3 ml

group. Parturients receiving 15 mg of spinal hyperbaric bupivacaine for

cesarean delivery developed a higher mean level and longer duration of sensory

analgesia than those receiving 12 mg (8). Fan et al. (9) examined four regimens

of combined spinal-epidural anesthesia in 80 parturients for cesarean section:

1. 2.5 mg bupivacaine 0.5% intrathecally combined with 22.2±4.6 ml of lidocaine

2% epidurally. This combination provided insufficient muscle relaxation. 2. 5

mg of bupivacaine 0.5% - spinally with 10.1 ±2.0 ml of lidocaine 2% epidurally

resulted in satisfactory anesthesia with rapid onset and minimum side effects.

3. Spinal 7.5 mg of bupivacaine 0.5% . 4. Spinal 10 mg

of bupivacaine 0.5%. Anesthesia in these groups (7.5 mg and 10 mg bupivacaine

0.5%) was mostly due to the spinal block. Their conclusion was that the

combined spinal-epidural technique, using 5 mg of bupivacaine and with

sufficient epidural lidocaine to reach a T4 level, had the advantages of both

spinal and epidural anesthesia with few of the complications of either.

Ciccozzi et al. (10) evaluated the combined spinal-epidural anesthesia by the

needle-through-needle technique in 40 parturients ( 1. Rawal N, Schollin J, Wesstrom G.

Epidural versus combined epidural block for cesarean section. Acta Anaesthesiol

Scand 1988;32:61-6 2. Covino BG. Rationale for spinal

anesthesia. International Anesthesiology Clinics 1989;27:8-12

3. Hunt 4. Marx GF, Lughx WM, Cohen S.

Fetal-neonatal status following Caesarean section for fetal distress. Br J

Anaesth 1984;56:1009-12 5. Alahuhta S, Kangas-Saarela T, Hollmen

AI, Edstrom HH. Visceral pain during caesarean section under

spinal and epidural anaesthesia with bupivacaine. Acta Anaesthesiol

Scand 1990;34:95-98 6. Riley ET, Cohen SE, Macario A, Desai

JB, Ratner EF. Spinal versus epidural anesthesia for cesarean section: A

comparison of time efficiency, costs, charges, and complications. Anesth Analg

1995;80:709-12 7. Vucevic M, Russell IF. Spinal

anaesthesia for Caesarean section: 0.125% plain bupivacaine 12 ml compared with

0.5% plain bupivacaine 3 ml. Br J Anaesth 1992;68:590-595

8. De Simone CA, Leighton BL, Norris MC.

Spinal anesthesia for cesarean delivery: A comparison of two doses of

hyperbaric bupivacaine. Reg Anesth 1995;20:90-94 9. Fan SZ, Susetio L, Wang YP, Cheng YJ,

Liu CC. Low dose of intrathecal hyperbaric bupivacaine

combined with epidural lidocaine for cesarean section - a balance block

technique. Anesth Analg 1994;78:474-7 10. Ciccozzi A, Iovinelli G, Varrassi G.

Effects of posture on the spread of local anesthetics in CSEA for Caesarean

delivery. Reg Anesth 1995;20:S74 11. Mok MS, Tzeng JI. Intramuscular

ketoralac enhances the analgesic effect of low dose epidural morphine. Anesth

Analg 1993;76:S269 12. Swami A, McHale S, Abbott P, Morgan

B. Low dose spinal anesthesia for cesarean section using combined

spinal-epidural (CSE) technique. Anesth Analg 1993;76:S423

13. Dickson MAS,

Jenkins J. Extension of epidural blockade for emergency Caesarean section.

Anaesthesia 1994;94:636-638 14. Westbrook JL, Donald F, Carrie LES.

An evaluation of a combined spinal/epidural needle set utilising a 26-gauge

pencil point spinal needle for Caesarean section. Anaesthesia 1992;47:990-2 Corning The first epidural anesthesia done by 1. Marx GF. The first spinal anesthesia:

Who deserves the laurels? Reg Anesth 1994;19:429-430 Bier August Bier (1), on August 24, 1898,

asked his assistant, Dr. Hilderbrandt, "to perform a lumbar puncture on

me", 8 days after he first performed it on a 34-year-old patient for

excision of a tuberculous capsule at the ankle joint. Bier wrote that he did

not feel any discomfort "except for a quick flash of pain in one leg at

the moment that the needle penetrated the meninges". Unfortunately, the

experiment was not successful because of an error (the syringe did not fit the

needle tightly... and consequently some CSF ran out and most of the cocaine was

lost). No sensory loss ensued. Dr. Hilderbrandt immediately offered to submit

himself to the experiment, which was successful. Both of them "went to eat

after the experiments were performed on our bodies. We had no physical discomfort, we ate, drank wine, and smoked several

cigars". However, next morning, after a one hour morning stroll Bier felt

slight headache which increased in intensity during the course of the day. Nine

days after the puncture, all the symptoms disappeared. After 3 more days, "I

was able to go on a train trip without discomfort and was fit enough to

participate in a strenuous 8 day hunting trip in the mountains". 1. Bier AKG, von Esmarch JFA. Versuche uber Cocainisirung des Ruckenmarkes. Dtsch Z Chir

1899;51:361-369 A new

look at the lumbar extradural space pressure The answer to the questions: Why does

not the Macintosh balloon indicator deflate, or why the hanging drop technique

is unreliable was given by Shah (1): The epidural space

pressure is influenced by many factors. It is raised by jugular venous

compression, ventilation with carbon dioxide and positive end-expiratory

pressure (PEEP). The lumbar extradural pressure is increased rapidly with

stimuli known to increase CSF pressure. However, the next question is what

happens in the "normal" condition (without jugular venous compression

or CO2 inhalation, etc.)? There is a wave pressure, which is the lumbar CSF

wave pressure transmitted to the epidural space. On that subject Shah quoted an

article by Hirai et al (2) published in 1982:"The arterial pressure wave

in the spinal CSF originates from the choroid plexus... The pulsatile vibration

of the brain parenchyma derived from the blood flow in the cerebral arteries

may have enough energy to generate the spinal CSF pulse. The amplitude of the

pulse wave varies directly with intracranial pressure". This citation is

not exactly true in the light of an investigation published by Urayama (3). He

performed system analysis on 16 adult mongrel dogs to determine the origin of

the lumbar cerebrospinal fluid pulse wave. The descending thoracic aorta was

occluded to evaluate the effects of the spinal arterial pulsations, and the

thoracic aorta and inferior vena cava were simultaneously occluded to evaluate

the effects of the spinal venous pulsations. It was concluded that, in the

first harmonic wave, the components of the lumbar cerebrospinal fluid pulse

wave are as follows: spinal arterial pulsations - 39.4%; spinal vascular

(arteries and veins) pulsations - 77%; venous pulsations in the spinal canal -

37.6%; and the intracranial pressure pulse wave transmitted through the spinal

canal from the intracranial space to the lumbar level - 23%. So, from this

investigation we can learn that 77% of the lumbar cerebrospinal fluid pulse

wave which is directly transmitted to the extradural space as an extradural

pressure wave is originated in the vascular system (arteries and veins), and

not in the brain . So, any rise in the blood pressure, which is not an

infrequent observation during epidural needle insertion, can give a concomitant

rise in the extradural pressure with the loss of the "negative"

pressure in the extradural space and "unreliable" hanging drop and

Macintosh balloon indicator techniques. 1. Shah JL. Positive

lumbar extradural space pressure. Br J Anaesth 1994;73:309-314.

2. Hirai O, Handa H, Ishikawa M. Intracranial pressure pulse waveform:

considerations about its origin and methods of estimating intracranial pressure

dynamics. Brain Nerve ( 3. Urayama K. Origin of lumbar

cerebrospinal fluid pulse wave. Spine 1994;19:441-445 Do not

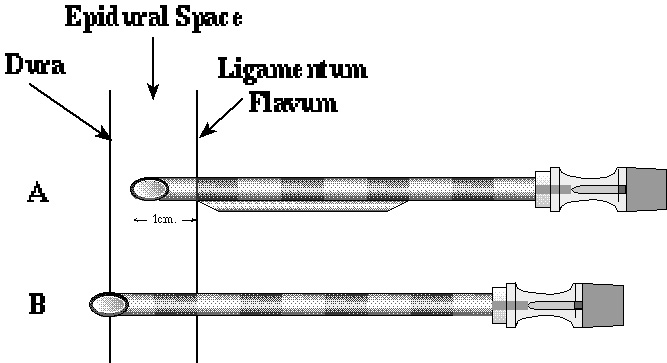

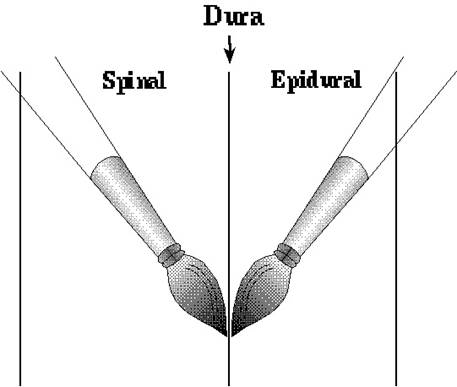

rotate the epidural needle The epidural needle rotation in CSEA

using the needle-through-needle technique was first suggested in 1988 by Rawal

et al. (1). However, Dr. Rawal abandoned this technique of epidural needle

rotation (2) because he was convinced that "180° rotation of the epidural

needle may cause dural tear". Nickalls and Dennison (3) found that the

distance the spinal needle has to be advanced past the end of the Tuohy needle

to just puncture the dura ranges from 0.3 to 1. Rawal N, Schollin J, Wesstrom G.

Epidural versus combined spinal epidural block for cesarean section. Acta

Anaesthesiol Scand 1988;32:61-6 2. Rawal N. Combined

spinal-epidural needle (CSEN) for the combined spinal-epidural block - reply.

Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 1989;33:618 3. Nickalls RWD, Dennison B. A modification of the combined spinal and epidural technique.

Anaesthesia 1984;39:935 4. Joshi GP, McCarroll SM. Combined

spinal-epidural anesthesia using needle-through-needle technique.

Anesthesiology 1993;78:406-7 5. Carter LC, 6. Meiklejohn BH. The

effect of rotation of an epidural needle. Anaesthesia 1987;42:1180-2 Epidural

rostral augmentation of spinal anesthesia Suzuki et al. (1) found that spinal

puncture with a 26G spinal needle, with no spinal anesthetic injection, immediately

before epidural injection of 18 ml 2% mepivacaine resulted in rapid caudal

spread of analgesia as compared to an epidural anesthesia alone. They

attributed it to the flow of local anesthetic into the subarachnoid space

through the perforation produced by the spinal needle. Dobson et al. (2)

reported of a sudden asystole 70 min after intrathecal injection of 2.75 ml

hyperbaric bupivacaine 0.5% in a patient whose cardiac output was being

monitored. After successful resuscitation , the height

of the block was judged to be T4. According to the authors of the report,

monitoring should continue for at least 90 min after induction of spinal

anesthesia. Bodily et al. (3) warned that changes in position can alter the

spread of sensory blockade for at least 1 hr after the intrathecal injection of

a hypobaric solution. They showed that 8 ml lidocaine 0.5% (baricity

0.9985±0.0003, 1. Suzuki N, Koyanemaru M, Onizuka S,

Takasaki M. Dural puncture with a 26-gauge spinal needle affects epidural

anesthesia. Reg Anesth 1995;20:S118 2. Dobson PMS, Caldicott LD, Gerrish SP.

Delayed asystole during spinal anaesthesia for transurethral resection of the

prostate. Eur J Anaesth 1993;10:41-43 3. 5. Serpell MG, Coombs DW, Colburn RW,

Deheo JA, Twitchell BB. Intrathecal pressure recordings due

to instillation in the epidural space. International Monitor on Regional

Anaesthesia 1993;52 6. Dell RG, Orlikowski CEP. Unexpectedly high spinal anaesthesia following failed extradural

anaesthesia for caesarean section. Anaesthesia 1993;48:641

7. D`Angelo R, 8. Barclay DL, Renegar OJ, Nelson EW. The influence of inferior vena cava compression on the level of

spinal anesthesia. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1968;101:792-800

9. Furst SR, Reisner LS. Risk of high spinal anesthesia following failed epidural block for

cesarean delivery. J Clin Anesth 1995;7:71-74 10. Gamil M. Combined

spinal/epidural anaesthesia for caesarean section. Anaesthesia 1994;49:545-6 11. Carrie LES. Epidural

versus combined spinal epidural block for Caesarean section. Acta

Anaesthesiol Scand 1988;32:595-596 12. Rawal N, Schollin J, Wesstrom G.

Epidural versus combined spinal epidural block for Caesarean section. Acta

Anaesthesiol Scand 1988;32:61-66 13. Rawal N. Single segment combined

subarachnoid and epidural block for Caesarean section. Can Anaesth Soc J 1986;33:254-255 14. Bromage PR. Mechanism of action of

extradural anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth 1975;47:199-212 15. Blumgart CH, Ryall D, Dennison B,

Thompson-Hill LM. Mechanism of extension of spinal

anaesthesia by extradural injection of local anaesthetic. Br J Anaesth

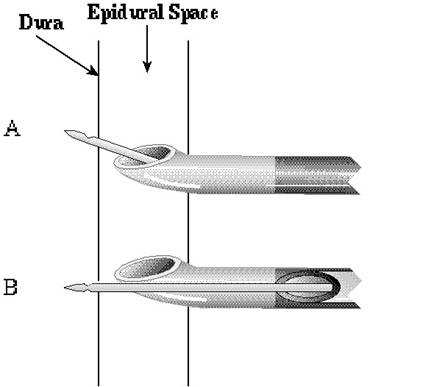

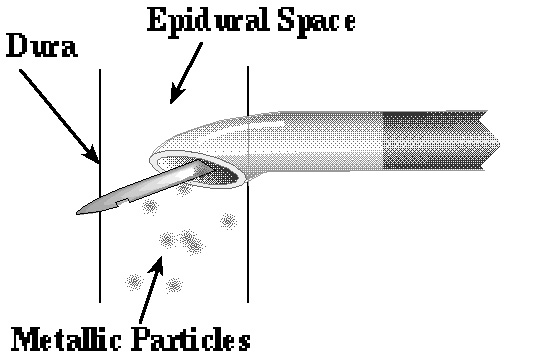

1992;69:457-460 Metallic

particles in the needle-through-needle technique The Tuohy needle was not originally

intended to be an introducer for a spinal needle. Tuohy (1) in 1944, used a

needle with a curved Huber tip for continuous spinal anesthesia, and Curbelo

(2) in 1949, adapted this needle for continuous epidural block. Coates (3) and

Mumtaz et al. (4) were the first to publish the possibility of inserting a long

spinal needle through a Tuohy epidural needle. They encountered only two

potential hazards, "possible passage of the epidural catheter through the

hole in the dura mater and the possibility of subarachnoid effects from

epidurally injected drugs by passage through the hole in the dura". Evans

(5) applied for a patent for this instrument a year later. The long spinal

needles have been available in the British market since 1985 (6). The forward

end of the spinal needle is inclined at an angle of about 30° to its length

when it projects by about 1. Tuohy EB. Continuous spinal

anesthesia: Its usefulness and technique involved. Anesthesiology 1944;5:142-143 2. Curbelo MM. Continuous peridural

segmental anesthesia by means of a ureteral catheter. Curr Res Anesth Analg

1949; 28:13 3. Coates MB. Combined

subarachnoid and epidural techniques. Anaesthesia 1982;37:89-90

4. Mumtaz MH, Daz M, Kuz M. Another single space technique for orthopaedic surgery.

Anaesthesia 1982;37:90 5. Evans JM. Instrument for epidural and

spinal anaesthesia: 6. Desira WR. A

special needle for combined subarachnoid and epidural block. Anaesthesia

1984;39:308 7. Kumar B, Messahel FM. Evaluation of

epidural needles. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 1987;31:96-99

8. Wigle RL. The

reaction of copper and other projectile metals in body tissues. J Trauma

1992;33:14-18 Superselective

spinal anesthesia Veneziani et al. (1) described a

technique of superselective spinal anesthesia for the surgical treatment of

saphenectomy. The block has been performed at L2-3 with the patients laying in

omolateral decubitus with respect to surgical side and injecting slowly 1%

hyperbaric bupivacaine 0.5-0.6 ml and maintaining such a position for about

10-15 minutes. The 24G Sprotte spinal needle was used with an incidence of only

0.4% postspinal headache. 1. Veneziani A, Santagostino G, Matera

D, Tulli G. Superselective spinal anaesthesia for the surgical treatment of

saphenectomy. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 1995;39:A430 CSEA in

uncommon disease Cherng et al. (1) described a case

report of combined spinal and epidural anesthesia for abdominal hysterectomy in

a 34-year-old woman with myotonic dystrophy. Patients with myotonic dystrophy

have a high risk of anesthetic complications, and the anesthetic technique

should aim to prevent any stimulation (chemical, mechanical or thermal), and avoid

any drugs that would induce uncontrollable muscular contraction (myotonic

crisis) (2). 1. Cherng YG, Wang YP, Liu CC, Shi JJ,

Huang SC. Combined spinal and epidural anesthesia for abdominal hysterectomy in

a patient with myotonic dystrophy. Reg Anesth 1994;19:69-72

2. CSEA for

laparoscopic operations Ciofolo et al. (1) evaluated the

respiratory effects of laparoscopy under epidural anesthesia in seven female

patients scheduled for a gamete intrafallopian transfer procedure. No

significant changes in the ventilatory variables were observed in the

Trendelenburg position. In contrast, CO2 insufflation significantly increased

minute ventilation (from 9.1±1.0 L/min to 11.8 ±2.6 L/min) and respiratory rate

(from 16.9±1.9 breaths/min to 23.1 ±3.3 breaths/min), whereas CO2 output

remained unchanged. PaCO2 remained constant throughout the study. They

concluded that epidural anesthesia may be a safe alternative to general

anesthesia for outpatient laparoscopy, as it is not associated with ventilatory

depression. Epidural analgesia for minilaparotomy cholecystectomy improves pain

relief in the immediate postoperative period, compared to intramuscular

morphine (2). Reduction of the surgical stress response can be achieved by two

techniques: One is to reduce the degree of tissue trauma and thereby the injury

response using the "minimal invasive surgery concept"; the other is

"stress-free anesthesia and surgery" providing effective pain relief,

including afferent neural block (3,4), together with block of various humoral

mediator cascade systems (arachidonic cascade metabolites, cytokines, etc.) as

well as a maintenance of nutritional status by provision of unspecific

nutrients (glutamine, arginine) or growth factors (growth hormone, etc.) (5). 1. Ciofolo MJ, Clergue F, Seebacher J,

Lefebvre G, Viars P. Ventilatory effects of laparoscopy under epidural

anesthesia. Anesth Analg 1990;70:357-61 2. Dahl JB, Hjortso N-C, Stage JG,

Hansen BL, Moiniche S, Damgaard B, Kehlet H. Effects

of combined perioperative epidural bupivacaine and morphine, ibuprofen, and

incisional bupivacaine on postoperative pain, pulmonary, and

endocrine-metabolic function after minilaparotomy cholecystectomy. Reg Anesth

1994;19:199-205 3. Kehlet H. Modification of responses

to surgery and anesthesia by neural blockade: Clinical implications. In:Cousins MJ, Bridenbaugh PO, eds. Neural blockade in

clinical anesthesia and management of pain. 5. Kehlet H.

Postoperative pain relief. A look from the other side.

Reg Anesth 1994;19:369-377 Postoperative

epidural analgesia Albert Schweitzer said that "pain

is a more terrible lord of mankind than even death itself". Bonica (1)

wrote that "acute and chronic pain afflicts millions upon millions of

persons annually, and in many patients with chronic pain and a significant

percentage of those with acute pain, it is inadequately relieved". In the

1980s, surveys of patients` subjective well-being revealed an incidence of

moderate or severe pain after surgery of 31-75% (2,3).

De Leon-Casasola et al. (4) compared the effect on postoperative myocardial

ischemia of epidural versus intravenous patient-controlled analgesia. 198

patients received either technique for 5-7 days postoperatively. Patients in

the epidural group had a lower incidence of tachycardia (14% vs. 65%), ischemia

(5% vs. 17%), and infarction - 0% vs. 20% of patients with ischemia in the

intravenous patient-controlled analgesia group. Postoperative ileus is an

undesirable response to injury and is predominantly caused by an increase in

inhibitory afferent sympathetic activity (5). Postoperative continuous epidural

analgesia may improve gastrointestinal motility and reduce ileus (6-9). Early

oral feeding reduced the risk of septic complications (10). The positive effect

of epidural local anesthetic analgesic techniques on gastrointestinal paralysis

may facilitate early oral nutrition as well as reducing fatigue and

convalescence. 1. Bonica J.J. History

of pain concepts and pain therapy. Mt Sinai J Med 1991;58:191-202

2. Kuhn S, Cooke K, Collins M, Jones JM,

Mucklow JC. Perceptions of pain relief after surgery.

Br Med J 1990;300:1687-1690 3. Owen H, McMillan V, Royowski D.

Postoperative pain therapy: A survey of patients` expectations and their

experiences. Pain 1990;41:303-307 4. De Leon Casasola OA, Lema MJ,

Karabella D, Harrison P. Postoperative myocardial ischemia: Epidural versus

intravenous patient-controlled analgesia. Reg Anesth 1995;20:105-112

5. Wattwill M.

Postoperative pain relief in gastrointestinal motility. Acta Chir Scand

1988;550(Suppl):140-145 6. 7. Sheinin B, Asantila R, Orku R. The

effect of bupivacaine on pain and bowel function after colonic surgery. Acta

Anaesthesiol Scand 1987;31:161-164 8. Ahn H, Bronge A, Johansson K, Ygge H,

Lindhargen J. Effect of continuous postoperative epidural analgesia on

intestinal motility. Br J Surg 1988;75:1176-1178 9.

Wattwill M, Thoren T, Hennerdal S, Garvill J-E. Epidural analgesia with

bupivacaine reduces postoperative paralytic ileus after hysterectomy. Anesth

Analg 1989;68:353-358 10. Unilateral

spinal anesthesia Using the needle-through-needle

technique in 80 patients for cesarean section Fan et al. (1) noted the

occurrence of a unilateral spinal block with the hyperbaric 0.5% bupivacaine,

"because keeping the patient in the lateral

position was necessary to accomplish the epidural procedure". 1. Fan SZ, Susetio L, Wang YP, Cheng YJ,

Liu CC. Low dose of intrathecal hyperbaric bupivacaine

combined with epidural lidocaine for cesarean section - a balance block

technique. Anesth Analg 1994;78:474-7 CSEA for

abdominal operations Guedj et al. (1) compared between spinal

anesthesia and combined spinal-epidural anesthesia (CSEA) in 63 patients

undergoing gynecological surgery. Spinal anesthesia (n=34) was carried out in

the L3-4 interspace with the patients sitting using 15 mg of hyperbaric 0.5%

bupivacaine with adrenaline. In the CSEA group (n=29) an epidural catheter was

inserted through the L2-3 interspace and the spinal anesthesia in the L3-4

interspace, while the patients were sitting. In the CSEA group, excellent

analgesia was obtained in all patients. In the spinal group, general anesthesia

was required in 3 patients (8.8%), as anesthesia only reached the T12 level in

2 cases, and as surgery lasted longer than the spinal in the third one.

Moiniche et al. (2) described a case of colonic resection with early discharge

after combined subarachnoid - epidural analgesia, preoperative glucocorticoids,

and early postoperative mobilization and feeding in a 59-year-old pulmonary

high-risk woman. They have introduced an epidural catheter between T9-10 and a

spinal catheter between L3-4. During the operation the patient was fully awake.

At one time during intestinal traction, visceral pain was treated vith

intravenous 100 æg

fentanyl. Surgery lasted for 70 minutes. The spinal catheter was removed at the

end of surgery, while the epidural catheter provided postoperative analgesia

for 72 hours. Luchetti et al. (3) used the combined spinal-epidural anesthesia

in 20 patients undergoing surgery for hernioplasty, saphenectomy,

hemorroidectomy and varicocelectomy. The subarachnoid injection consisted of

hyperbaric bupivacaine 1% 1 ml and the epidural catheter injection -

bupivacaine 0.5% 3 ml + fentanyl 50 µg. Analgesia was excellent in 17 patients

and good in 3. No patient needed further analgesic medication intraoperatively.

Mihic and Abram (4) compared five groups of patients undergoing abdominal

hysterectomy with or without appendicectomy with regional anesthesia. Two

hundred patients were divided as follows: Group 1 - spinal anesthesia with

hyperbaric 0.5% bupivacaine; Group 2 - as group 1 with the addition of 0.06 mg

of IV buprenorphine and 2.5 mg of IV midazolam; Group 3 - epidural block with

0.75% bupivacaine; Group 4 - as group 3 with the addition of epidural morphine

1%; Group 5 - combined spinal-epidural block (as in groups 1 and 4). No case of

unsuccessful blockade occurred in the combined spinal-epidural anesthesia,

compared to 3-4 cases of failed block in the other groups. Four patients whose

analgesia was considered to be unsuccessful had to be intubated to obtain

satisfactory surgical conditions. The combination of subarachnoid and epidural

block provided the best analgesia. 1. Guedj P, Eldor J, Gozal Y.

Conventional spinal block versus combined spinal-epidural anaesthesia for lower

abdominal surgery. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim 1992;11:399-404

2. Moiniche S, Dahl JB, Rosenberg J,

Kehlet H. Colonic resection with early discharge after combined

subarachnoid-epidural analgesia, preoperative glucocorticoids, and early

postoperative mobilization and feeding in a pulmonary high-risk patient. Reg

Anesth 1994;19:352-356 3. Luchetti M, Palomba R, Liardo A,

Bardari G, Sica G. Combined spinal-epidural anaesthesia (CSEA) is effective and

safe for minor general surgery. Int Monitor Reg Anaesth 1994;A97

4. Mihic DN, Abram SE. Optimal regional

anaesthesia for abdominal hysterectomy: Combined subarachnoid and epidural

block compared with other regional techniques. Eur J Anaesthesiol 1993;10:297-301 CSEA for

thoracic operations Kowalewski et al. (1) reported on the

use of spinal anesthesia with hyperbaric bupivacaine (20-30 mg) and/or

lidocaine (150 mg) with morphine (0.5-1 mg) combined with general anesthesia

with alfentanil 97 ±22 µg/Kg and midazolam 0.04±0.02 mg/Kg supplemented with a

muscle relaxant and maintained with isoflurane (0.25-0.5%) in oxygen in 18

patients for coronary artery bypass surgery (CABG). They suggested that general

anesthesia combined with spinal anesthesia may be an effective technique for

CABG. Very low concentrations of inhalational agents are required to maintain

unconsciousness during high spinal anesthesia (2). Epidural anesthesia

attenuates the endocrine-metabolic responses to surgical stress (3), reduces

intestinal paralysis (4,5) and decreases perioperative

morbidity (6,7). Thoracic epidural anesthesia decreases heart rate, mean

arterial pressure, cardiac output and left ventricular contractility (8,9). Dopamine effectively counters cardiovascular depression

during thoracic epidural anesthesia (10,11). Dopamine

effectively and dose-dependently counters cardiovascular depression induced by

the anesthetic technique of combining isoflurane and thoracic epidural

anesthesia (12). Animals` experiments demonstrated that spinal cord section

(13) or its cooling at the T1 level (14) resulted in behavioral and

electrophysiological evidence of sleep. Subarachnoid bupivacaine blockade

decreased the hypnotic dose of thiopental from 3.40 ±0.68 mg/Kg to 2.17±0.48

mg/Kg. The ED50 value of midazolam also decreased with bupivacaine blockade,

from 0.23 mg/Kg to 0.06 mg/Kg. It was suggested that the reduction in hypnotic

requirements was due to the decrease in afferent input induced by spinal

anesthesia (15). Extension of the segmental block to involve the

cardioaccelerator fibers (above T4) is commonly advanced as a reason to explain

the bradycardia that may accompany epidural analgesia (16), however, central

volume depletion may have a greater cardioinhibitory vasodepressor influence

(16,17). 1. Kowalewski RJ, MacAdams CL, Eagle CJ,

Archer DP, Bharadwaj B. Anaesthesia for coronary artery bypass surgery

supplemented with subarachnoid bupivacaine and morphine: a report of 18 cases.

Can J Anaesth 1994;41:1189-95 2. 3. Kehlet H. Modification of responses

to surgery by neural blockade: clinical implications. In: Cousins MJ,

Bridenbaugh PO, eds. Neural bloclkade. 4. Scheinin B, Asantila R, Orko R. The

effect of bupivacaine and morphine on pain and bowel function after colonic

surgery. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 1987;31:161-164 5.

Ahn H, Bronge A, Johansson K, Ygge H, Lindhagen J. Effect of continuous

postoperative epidural analgesia on intestinal motility. Br J Surg 1988;75:1176-1178 6. Yeager MP, Glass DD, Neff RK,

Brinck-Johnson T. Epidural anesthesia and analgesia in high-risk surgical

patients. Anesthesiology 1987;66:729-736 7. Scott NB, Kehlet H. Regional

anaesthesia and surgical morbidity. Br J Surg 1988;75:299-304

8. Reiz S, Nath S, Ponten E, Friedman A,

Backlund U, Olsson B, Rais O. Effects of thoracic epidural block and the

beta-1-adrenoreceptor agonist prenalterol on the cardiovascular response to

infrarenal aortic cross-clamping in man. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 1979;23:395-403 9. McLean APH, Mulligan GW, Otton P,

MacLean LD. Hemodynamic alterations associated with epidural anesthesia.

Surgery 1967;62:79-87 10. Lundberg J, Biber B, Henriksson BA,

Martner J, Raner C, Werner O, Winso O. Effects of thoracic epidural anesthesia

and adrenoreceptor blockade on the cardiovascular response to dopamine in dog.

Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 1991;35:359-365 11. Lundberg J, Norgren L, Thomson D,

Werner O. Hemodynamic effects of dopamine during thoracic epidural analgesia in